Bruce Rogers, a geologist and cave explorer from since he was a teen, came to us in September of 2015 to talk to us about caves. This was our last talk at the Exploratorium this year. The talk got off to a rocky start with not one but two fire alarms going off! We only had to evacuate once, but we were impressed by how many people (easily 90%) stuck it out.

Bruce starting with a definition of caves as underground, naturally occurring, with some parts in darkness, and humanly accessible. They have fascinated humans since probably long before we were even “human” (if the recent cave findings in South Africa have any bearing). For us they represent beauty, danger, and adventure, where of course for a long time they were likely refuges and homes.

Beyond that, to science and wider human interest they are even more interesting — they are geological repositories, they are workshops of evolution, they are archaeological sites, and holders of cultural treasures.

California has a few different types of caves across its landscape: limestone/marble caves, tafoni wind caves (tafoni is an italian word for small grottos built overlooking the ocean), sea caves, and fissure caves.

The ecology of caves can often be novel and fascinating, with new species often being described when new caves are found. Microbiology provides another level of this — with astrobiologists of late showing great interest in finding how life can live on in places like this, and where we might expect to find things alive on places like Mars.

There are creatures like the California giant salamander, one of the few salamanders to make noise. And of course bats — which Bruce in his cave explorations is careful not to disturb.

One cave near Monterey bay contained a graveyard of skunks, the skeletons of several thousand were found there in 1942. The skunks no longer seem to come back, but there are bats still in the cave. Mountain lions make use of caves in Big Basin.

Of course, all these caves are fragile, and their conservation is always a concern. He showed one example of cave that was discovered in 1954 (through an accident where someone got stuck, it soon became widely known) by 2007 everything had been broken off, the floors sledgehammered, full of garbage, and walls of graffiti. Spelunkers are now pretty wary of telling people of their finds, and recent caves opened to the public go to great lengths to preserve them from the outside. Caves do not renew — or at least not on any timescale we live on.

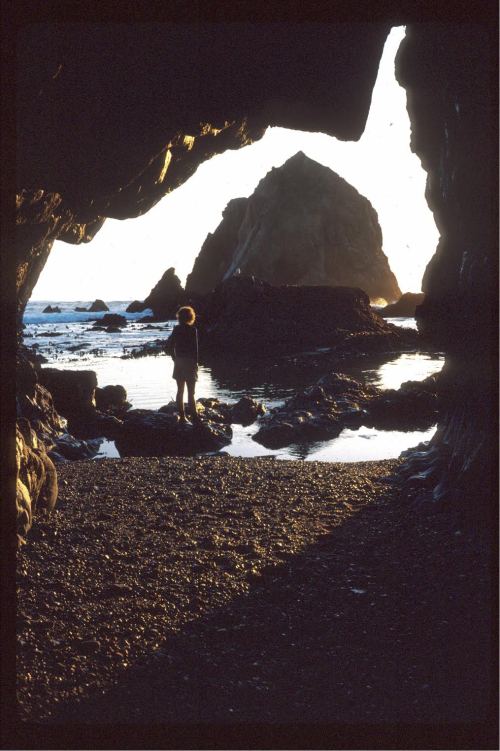

Sea caves are by far the most common type of cave in the Bay Area, created by the impact of waves along the bases of cliffs. Waves bring a tremendous amount of force to bear on cliffs. During hurricanes it can be enough to bend steel and smash concrete — but even a normal wave brings a lot more pressure to bear than most human activity.

Sea caves can be full of life, fish, seaweed, snails, limpets, anemones, mussels, barnacles, abalone, sea stars, sea lions (seals apparently don’t like caves). They can also be full of sand — the season, tide, and wave action can completely change a cave (he showed one picture of a cave with people standing upright in, and the next was someone crawling through the sand).

If you have an inclination to visit one — be wary! Be careful about the tide, and only go at extremely low tides.

There may be things to discover as well — At least there was… in 1927, a couple recovered some stolen silver in one of the sea caves. A stash of stolen goods from Hotels through San Francisco.

The Farallones also have some caves, quite large ones, with endemic species of a cave cricket and a salamander, and some very uncommon stalactites, and beautiful flowstone.

The only fissure cave he talked about is now on private land. There are not many limestone caves in the region either. The other most common cave type you will find in the Bay Area are tafoni caves — Castle Rock State Park have good examples, as well as Mt Diablo, and the Vasco Caves. The Vasco caves are part of a closed preserve: they have some 2000-4000 year old cave paintings and rare wildlife and plant species. You can get naturalist led tours of it in Spring and Fall.

If you want to know more about caves, preserving and exploring them, Bruce pointed us towards http://caves.org/